Having spent over six weeks in the Maritime provinces, we have learned a lot about Canada’s history. The British, the French and the Acadians all came and settled on land that the Mi’kmaq have called home for time immemorial. There was often conflicts between all four groups as they sought to access the land and its resources. When we arrived in Cape Breton Island in northern Nova Scotia, we encountered the presence of yet another European group who immigrated to Canada, the Gaels from northern Scotland.

Like many other immigrants, the Gaels left their homes in Europe seeking a better life. Many of them wanted to possess their own land and not be beholden to the large landowners. They settled in Cape Breton Island in the late 1700s and early 1800s and their culture is still present today.

Our visit to the Bailenan Gàidheal, the Highland Village Museum in Iona, NS, gave us some insights about the Gaels, their history and their culture. This living history museum is on 43 acres overlooking the Bras d’Or Lake and is about 30 minutes from Baddeck, NS.

When we arrived at the Visitor Center, we were welcomed in Gaelic and given an orientation to the museum and some instructions as to how to proceed. The Village consists of 12 buildings that represent four eras in the Gaelic community’s history.

Our walking tour began at the Black House, a stone hovel in Scotland. When we entered, there was a woman there dressed in period attire that talked to us about what was happening in the region in the late 1770s. She reflected on how life had become so difficult and how many were starving due to the rising rents that they had to pay the landowners. She said that many were leaving and crossing the ocean where they were guaranteed land of their own.

The second house was a log cabin that the new arrivals built in Cape Breton from the 1770s-1850s.. The woman discussed the journey to Cape Breton and their disappointment when they found that their land was heavily forested. They had thought that it would be good farmland but it had to be cleared before they could plant anything. She said that those who had come over ahead of them helped them survive their first winter. They worked together and formed a strong community in this new land.

Another house was a much nicer home with a center chimney. When we entered, we were greeted by a group of people who had gathered for a ceilidh, a social gathering. We were invited to join them. One lady told us a story and another played the fiddle while all sang. This tradition is still practiced today throughout Cape Breton.

By the 1850s the Gaels started to build churches and larger homes and establish businesses in the area. They began to interact more with other non-Gaelic speaking communities. Some of the young people left the community and migrated to the New England states in the U.S.

The final era and group of structures represented the changes in the Gaelic community from the 1880s to the 1920s. During that period, Nova Scotia built schoolhouses and the children received instruction only in English. If a child spoke Gaelic, they were punished.

There were more specialized businesses that opened like the general store, a forge, a hardware store, a saw mill, and a carding mill and more interaction with the people outside of their community.

In the general store there was a wide variety of goods for sale.

The operational saw mill has been making shingles in the community for years. We got to see how they made them and the gentleman there said that we could even take one home if we wanted.

Outside the Turn of the Century House, the women and a man were washing wool and laying it out to dry before taking it to the carding mill to be processed.

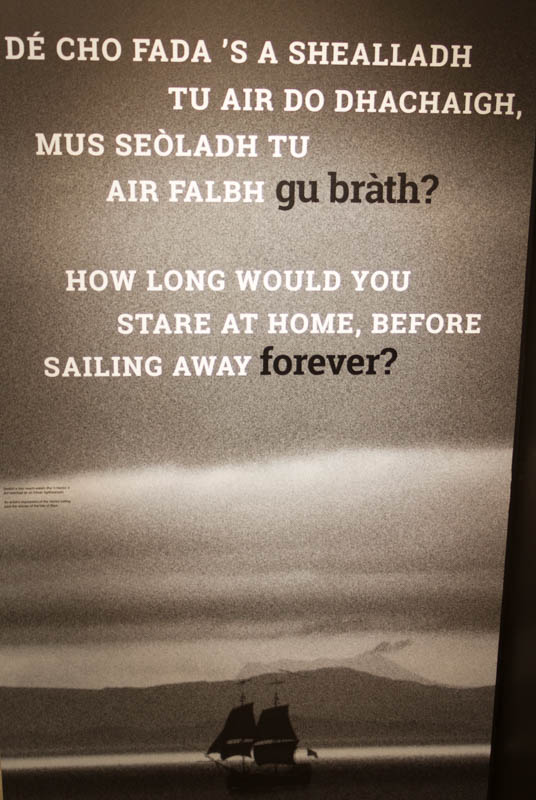

The carding mill at the museum is the oldest continuously operating mill in North America. It came from Worcester, MA and it bears the patent date of 1869.

Interestingly, a large number of the buildings are original and were relocated to this site. One of them was even moved by barge to the museum’s property. All of the artifacts are locally sourced as well. The interpreters in each building are paid staff, not just volunteers, and are dedicated to preserving the Gaelic community and its heritage.

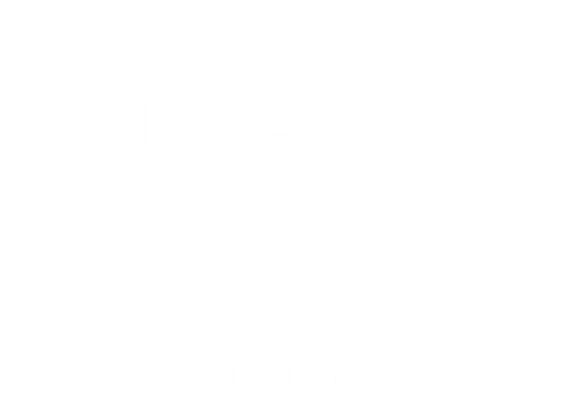

At the end of the walking tour, we came back to the Visitor Center where there was information about what the Gaelic community is doing to revive interest in their culture and history which declined in the 20th century. At the beginning of the century, the number of Gaelic speakers in Nova Scotia was about 50,000 but there are only about 2,000 today. There are organizations that are making strides in preserving the language and culture. Currently in some of the schools they do teach Gaelic and we saw many signs, including road signs, throughout the region in both English and Gaelic.

We found our tour of the Highland Village Museum to be fascinating. We thought that it was a very educational experience and well worth our time.

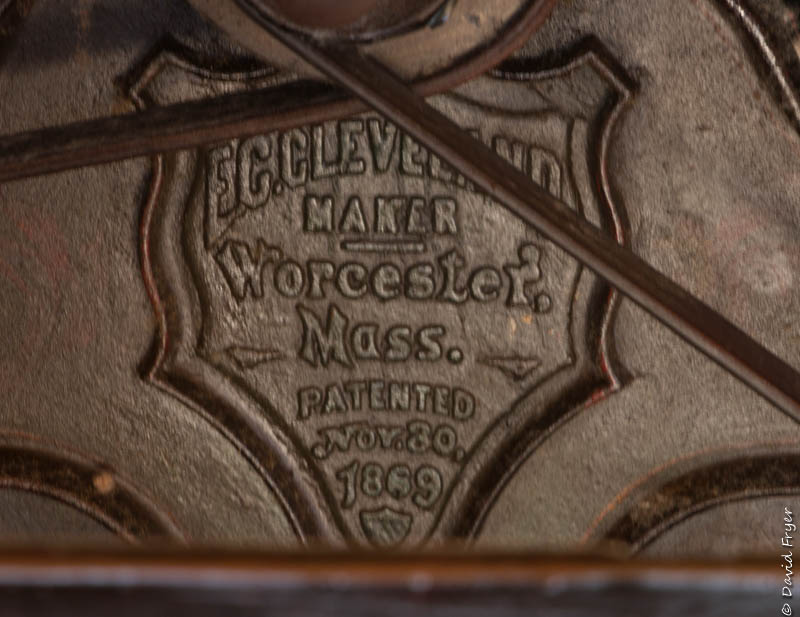

There is a Gaelic College in St. Ann’s, NS, which is also about 30 minutes from Baddeck. Founded in 1938, the non-profit College called Colaisde na Gàidhlig, focuses on preserving Gaelic culture. Their mission is “to promote, preserve, and perpetuate through studies in all related areas: the culture, music, language, arts, crafts, customs and traditions of immigrants from the Highlands of Scotland.” At the Visitor Center in Baddeck, we learned that every Wednesday at 7:30 p.m. during the summer the College hosts a ceilidh (pronounced “kay-lee”). We thought that this would be a perfect place to go to experience this music tradition.

The concert that we attended was in Mackenzie Hall and featured Kimberley Fraser (an award-winning fiddle and piano player who has recorded several albums and also teaches at the College), Hilda Chiasson (an internationally acclaimed piano player), Aaron Lewis (a singer-songwriter who plays a variety of instruments and inducted into the Nova Scotia Country Music Hall of Fame in 2018), Michael Cavenaugh (a singer-songwriter who sings and plays fiddle, mandolin, and guitar), and Joyce MacDonald (a Gaelic language instructor at the College). All of them were renowned musicians and instructors from the College and the Gaelic community. They told stories, sang and played the fiddle, guitars, and keyboard. They were extraordinary. We thoroughly enjoyed this cultural event.

Oftentimes when we are traveling we come cross something that is unexpected. The presence of the Gaels in Cape Breton was surprising. We were glad that we got to experience some of their cultural traditions.